[note: Check out the glossary below for a definition of relevant terms]

Last week, we finally managed to do scans with Bluesky on the MOUSE. This is a major milestone in our migration project, and it opens up a host of new possibilities and efficiency improvements. So let’s talk a bit about it.

What Bluesky is (and isn’t)

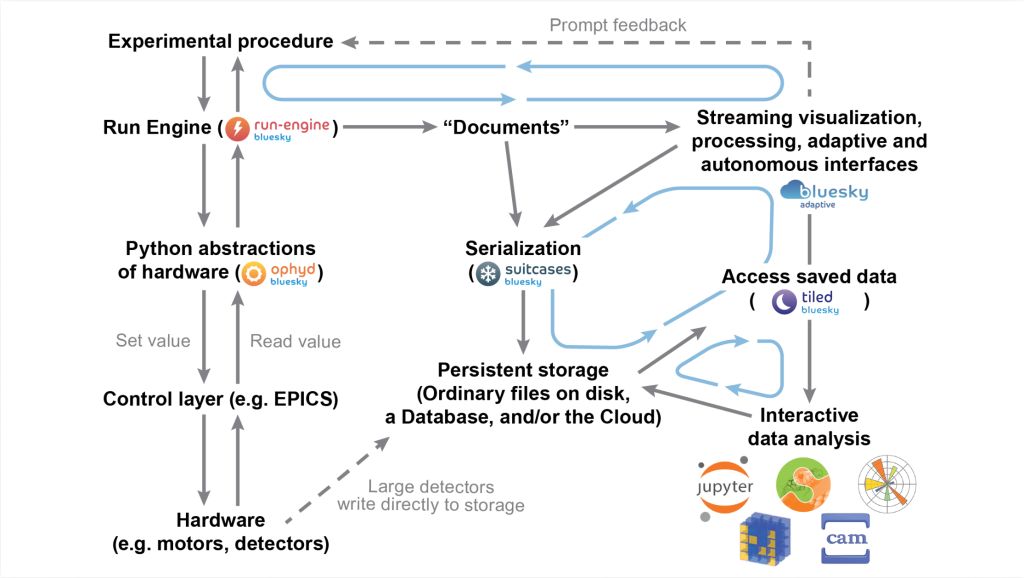

As far as my current understanding goes, Bluesky is both the name of an ecosystem and an experimental orchestrator (“Run Engine”) contained within. The Bluesky ecosystem is a set of python libraries and extensions that lets you perform complex experiments on automated hardware, up to and including closed-loop automated (material) optimization experiments. Imagine, for example, and experiment where you automatically tune the synthesis parameters of an in-line synthesis, until you get the properties you are looking for. This requires a lot of hardware organisation, dealing with information streams from many events, and possibly live processing feeding parameters back into the Run Engine.

Doing this flexibly benefits from a modular set-up of the ecosystem, adding easy extensibility and enabling support for a diverse spectrum of machines. That way you can implement the components that matter for your application without unnecessary baggage, and change and adapt what you need to get it going on your machine. The benefit to leveraging the Bluesky ecosystem for this is that you do not have to do the brunt of the work, and that you enable functionality that you would otherwise not have bothered developing.

For the MOUSE, we have been operating for a year last year without Bluesky, just using plain EPICS and python scripting. While this is possible to do and initially seems to be the path of least resistance, we end up at a point where we repeatedly have to concern ourselves with specific timings of events and programming functionality that already exists such as live views and adaptive scanning methods. So in the long run, it makes sense to invest a little time now to get Bluesky running, to reap the benefits of the work from its large and active international team of developers later on.

If you are looking for a nice user interface, you’re unfortunately in the wrong place. This is a power tool for orchestrating complex hardware in a near-infinitely flexible manner, and that is something that can only be achieved using a command-line interface. For limited use cases, however, a custom UI can be added on top to help the more casual user use the system, optionally with an LLM for simplifying customisation.

Prerequisites on MOUSE-like instruments

Before we could get going with the Bluesky Run Engine, we needed to make sure all the necessary devices can be controlled by it. That meant making sure we could abstract the devices using the ophyd interlayer. There are several ophyd device abstractions available already for devices that talk on the EPICS communication bus, either directly or via Diamond’s Dodal.

We needed to get the following parts working:

- The Xenocs X-ray generator voltage and current readout and shutter control, these are communicating with Modbus over ethernet. For this, I wrote a custom EPICS IOC using caproto.

- The slit motors with integrated motor controllers, in our instrument, these are Schneider Electric (now Novanta) IMS MDrives, communicating using a RS422 serial bus (connected via ethernet). This model is supported by the excellent synApps collection of EPICS drivers.

- We swapped out the motor controllers of our Newport sample stage for SMC100PP Newport motor controllers, which are also supported under synApps. While our (genuinely good) 6-axis Trinamic motor controller is still in place for the few PI motors we have, the caproto EPICS IOC I made for them is unfortunately not completely behaving like a motor IOC should, and I don’t have time to fix it, so we leave that for now.

- The beamstop and detector motors are controlled by IMS MForce controllers, equally supported by synApps.

- For the pressure gauge, Abdul Moeez wrote a caproto IOC during his time here, which can be downloaded from here

- The vacuum and air valves, as well as temperature readouts are controlled using an Arduino Pro Portenta Machine Control, for which I wrote the embedded code, and an accompanying caproto IOC.

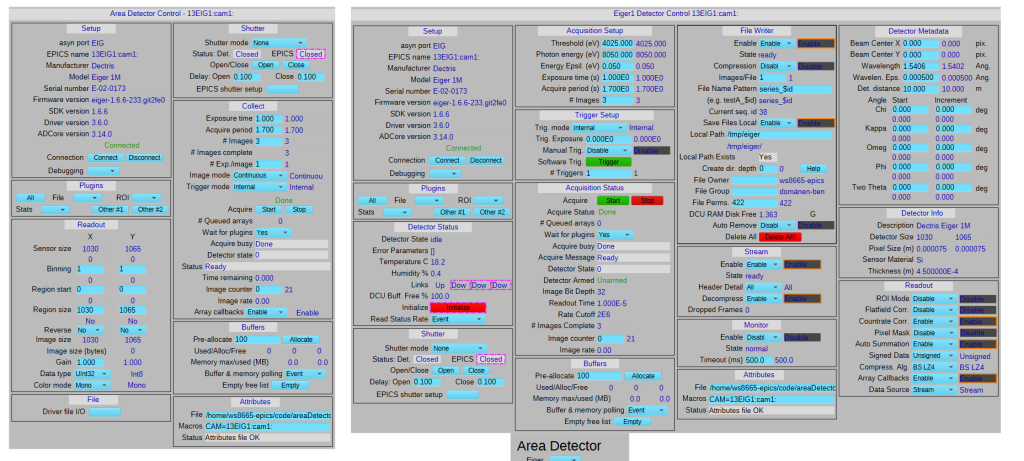

- The Dectris Eiger R 1M (first generation) was the last piece of the puzzle, for which we have one working solution now in the form of the large AreaDetector EPICS library. This library has support for a lot of detectors, including our PoE Allied Vision Mako optical cameras. It is a bit of a faff to get working as there are many options and plugins, and the detector only works if everything is configured just right, but we managed to get this going. We are also investigating the promising Odin+FastCS solution that the Diamond Light Source has developed as an alternative. Ophyd has AreaDetector support for Eiger detectors, so we’re good there.

We have more hardware connected to the EPICS bus, but this is optional for use in experiments and not a showstopper for bluesky. This includes:

- stall-detecting, powerful Harvard PhD syringe pumps

- a decent IKA hotplate/stirrer

- a balance, not named because I’m not too happy with its error-prone communication

- a problem-free Watson Marlow peristaltic pump

- a flexible but unfortunately no longer produced Lauda temperature controlled water bath, with an operating range between -50 to 200C

Hardware waiting for integration (i.e. will be done if there’s a need) includes:

- A Keithley 2460 sourcemeter for integrated electrochemical experiments

- Omron temperature controllers

- A host of rescued, older measurement equipment including electrometers, impedance spectrometers, multimeters and power supplies. Most of these communicate over GBIP, but I’d need a GPIB-to-ethernet converter first.

- An autosampler

The progress so far

So after spending the occasional afternoon on gradually adding devices to the EPICS communications bus, lsat week we finally got to the stage where the main devices were operational.

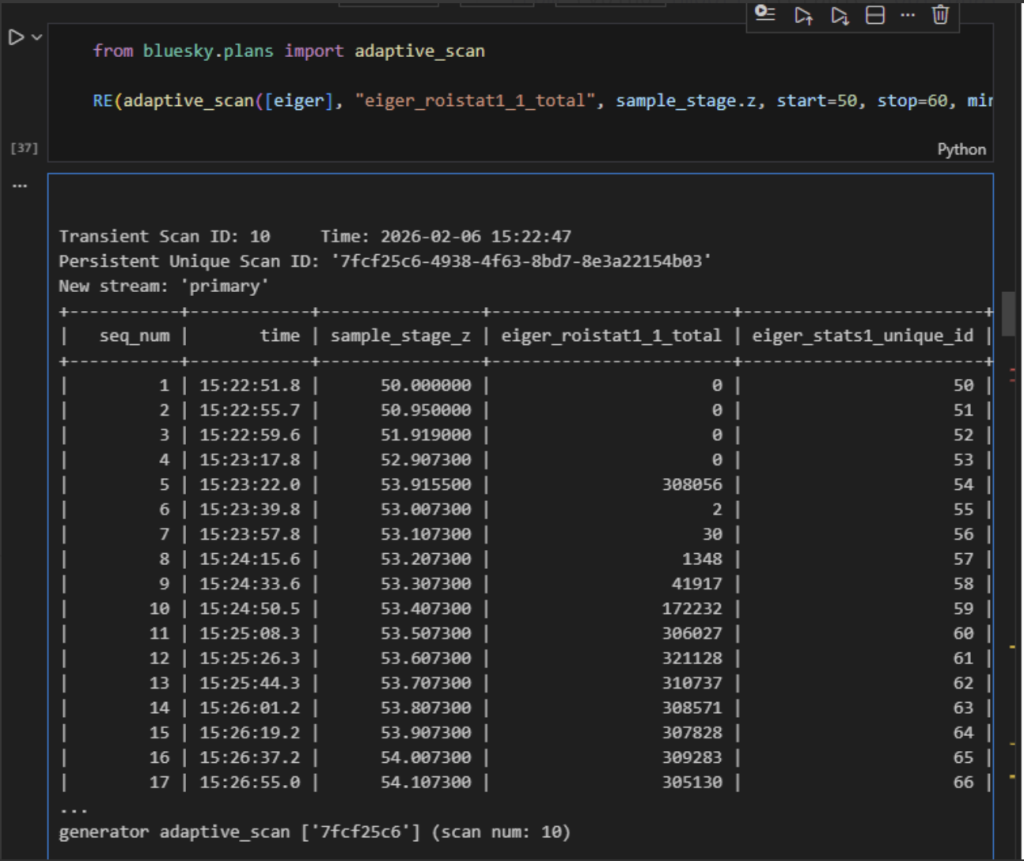

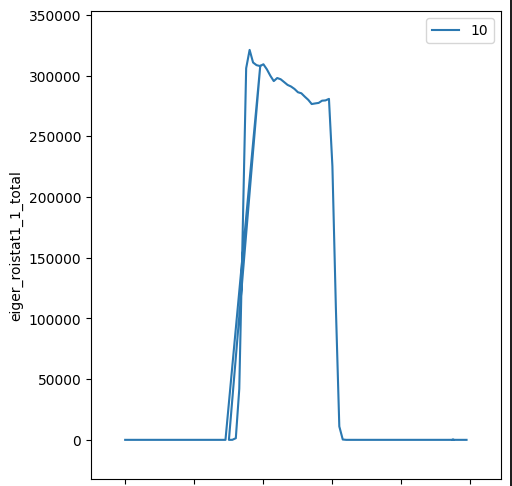

From there, it was a short hop and a skip to implement the ophyd devices, the Tiled database for storing the event records, and adapting the Bluesky example scans to our hardware. The second scan we did was, of course, an adaptive scan to show off the capabilities. This is a scan which uses large steps, but in areas of interest, (goes back and) uses finer spacing to better characterise the transition region. Scanning over a sample, that meant we got the following scan:

So in the coming period, we’ll be experimenting more with this, and gradually transitioning some operation to this interface. In particular the operando, in-situ, scanning and mapping experiments stand to benefit from this, whereas our well-functioning solid and powder sample measurement procedures are probably the last to go. We will have a closer look at the Bluesky queueserver, which will then take over significant work from our own measurement sequencing methods, with the added benefits of being able to remotely track and manage the scheduled measurements.

Lastly, we will need to discuss with our internal teams whether it makes sense to set up a more permanent local facility (Tiled?) server to act as a database for event streams from automated platforms. While these don’t hold the primary data of the experiment (these are stored in our ridiculously extensive HDF5 files and catalogued in the institute’s OpenBIS database), they do track what is going on and therefore provides valuable metadata that can help with complex searches, live activity views, troubleshooting and traceability.

Glossary

Let’s define the relevant terminology from bottom to top:

- Hardware device: These are motors, detectors, vacuum pumps, chillers, X-ray generators… all the bits that make up a machine

- Hardware communications interface: This is how the hardware communicates with the outside world. You’re probably most familiar with the USB interface. In our lab, however, we prefer hardwired ethernet ports, and old-fashioned serial ports (such as RS232, RS485 and RS422), which are reliable when you have large numbers of connections.

- Hardware communications protocol: This is the “language” that each device uses to communicate. For ethernet, this could be TCP/IP, but also EtherCAT (very low latency, requiring a separate network).

- Hardware communications protocol overlay: Each hardware has different things to set and read, and many manufacturers do this communication in their own way. There are a few old standards like Modbus, UART and SCPI, both of which can be sent over serial or ethernet. There are also newer standards appearing like EtherCAT and OPC-UA. For USB, the protocol is often closed-source, needing a manufacturer-supplied communications library (invariably Windows) DLL to work: a second reason we’re no big fans of USB.

At this point, you see that things start ballooning very rapidly. If you want to orchestrate hardware in an instrument, you do not want to deal with all of these variations separately, if at all possible. Fortunately, this is where we can start reducing complexity a bit:

- EPICS: A communications layer that translates each individual hardware communications to a unified protocol over a shared communications bus. That means that simple parameter-value pairs (EPICS-PVs) from each hardware device can now be set and read in the same way. These PVs support all kinds of attributes such as warning and alarm limits, operating limits, units, and much more.

- Ophyd device: a Python layer that bundles all communication for a hardware device (or a contiguous group of hardware devices such as a grazing incidence sample stage) into logical groups. It exposes each group in the same way, allowing you to stage, trigger, unstage and read each device, regardless of whether this is a detector or a temperature controller. There are synchronous or asynchronous ophyd devices available, these can be mixed and matched as desired.

- Bluesky Run Engine: an experiment orchestrator, basically a python interface with some added niceties, that runs experimental plans.

- bluesky plans: These experimental plans are sequences of operations on ophyd devices. Many experimental plans and plan stubs exist already that execute regular tasks, like scans (e.g. linear, logarithmic, grid, spiral, and adaptive scans, which can scan any “scannable” device, such as motors or temperature stages).

- bluesky-queueserver: You want plans run in sequence? this is the place to be. The queueserver can prioritize, rearrange, and much more.

- Tiled: All the actions in Bluesky emit streams of messages and metadata. This is handled by a databroker like Tiled, which offers a database that can be polled for events matching a number of criteria.